Monster Mania: The Tragedy of Alma Wade

Monster Mania is a weekly column celebrating the unique and varied monster designs in horror gaming.

Scary kids have always been an effective tool in horror. Sorry, parents, but facts are facts. Whether it is J-horror starlets such as The Ring’s Samara or The Grudge’s Kayako, these long-haired horrors have cemented their place amongst genre icons. The difficulty in this horror trope transitioning from film to games is ensuring it remains effective for an experience far longer than the length of a feature film. An experience that hopefully amounts to more than a series of uninspired jump scares.

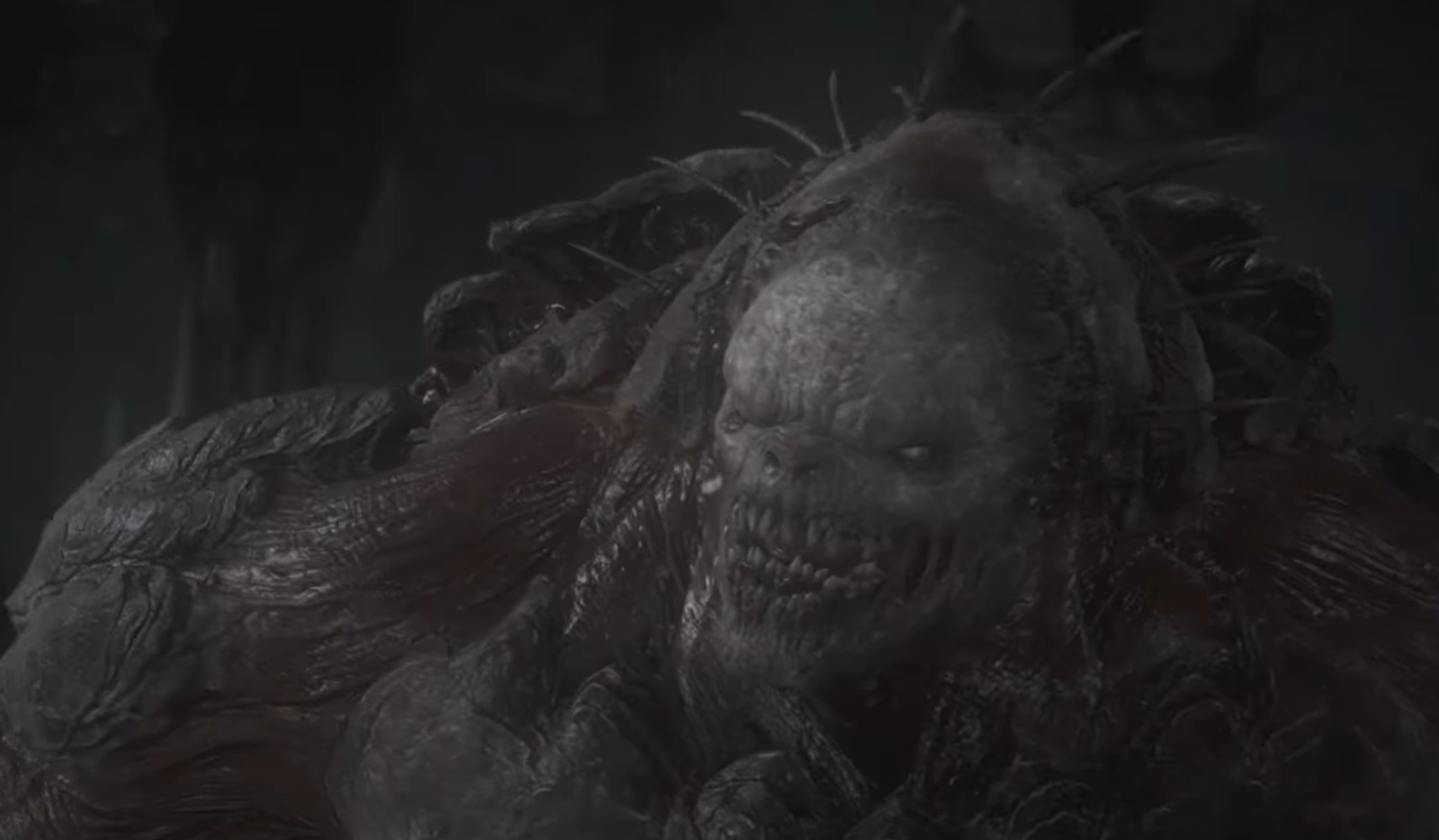

There are few better examples of a studio understanding how to blend and utilize genre tropes better than Monolith Studios’s 2005 horror first-person shooter masterpiece, F. E. A. R. (aka First Encounter Assault Recon). F. E. A. R. smartly utilized the spooky kid trope to bring its haunting antagonist, Alma Wade, to life but gave this “monster” more depth and significance rather than delivering another J-horror hatchet job. Alma is a little girl with psychic powers, whose signature long black hair covering her face and red dress contrasts against F. E. A. R.’s Merc-filled world of mundane office parks and gunmetal gray color palette.

Monolith’s ingenuity in pacing scares and fleshing out her character allowed Alma to grow into her role as a figure of central importance to the narrative rather than simply serving as a cheap jump scare machine.

That being said, the player’s first few interactions with Alma are what you’d expect from a creepy little girl being the main antagonist.

Early on, F.E.A.R.’s protagonist, the Point Man, begins experiencing hallucinations and psychic events. Figures walk into rooms only to dissolve into ash a moment later. Lights will flicker. Strange whispers will be uttered. Certified tropes of the genre, but as with most tension-building techniques, it is more important how and when they are utilized rather than being measured simply by their substance.

As such, Alma is initially the source of jump scares: She’ll emerge suddenly from the shadows of a doorway, crawl at the player in a dark vent, or suddenly appear on a CCTV monitor. These moments are mostly an amalgamation of familiar scare styles but a suitable primer for F.E.A.R.’s approach to horror and are expertly placed to break up the game’s numerous and deliciously destructible gun fights.

While following bloody footprints or having a creepy girl suddenly run at the player can be effective, if that were all Alma delivered, F.E.A.R. wouldn’t be as highly regarded as it is. Smartly incorporating and picking opportune moments to insert these horror elements allows F.E.A.R.’s narrative to evolve into something more compelling than your typical generic military shooter.

Uncovering Alma’s origin and history allows the character to feel like a proper “monster” rather than a cheap prop. The most memorable of monsters are those with a greater significance than JUST looking creepy. And this is why Alma feels like a proper addition to the pantheon of spooky kid genre icons, as her origin is as chilling as her penchant for suddenly appearing is.

A few years after her birth, Alma began exhibiting strong psychic powers that her father and A.T.C. (Armacham Technology Corporation) C.E.O. Harlan Wade wished to exploit. From the age of three, Harlan Wade imprisoned his daughter within Armacham’s super lab facility Project Origin, in an attempt to harness her powers. As with most monsters, the creator is often the more monstrous of the duo, and in Harlan Wade’s case, this would be an understatement. He would eventually permit A.T.C. to use Alma as a breeding machine for other psychic beings. A decision he made when she was still a child.

This is why, when referring to Alma as a “monster,” I do so in quotes. A character initially introduced as a source of terror, seemingly taking joy in flaying flesh from bone. But as the player’s journey progresses, they learn that Alma is a tragic figure whose rage you not only come to understand but feel is justified.

Monolith also made the conscious decision not to have the player directly fight Alma. Deciding to spare the player from a traditional boss fight against Alma, Monolith gives credence to just how tragic of a figure she is. And in that tragedy, her status as the series “monster” feels in line with the best of haunting horrors and ghostly figure tropes that accompany them. A failure to give significance to these types of characters often results in an overreliance on their inherent jump scare potential, relying solely on their appearance, when the true horror lies within their backstories.

For more horror game reviews, opinions, and features, check out DreadXP.