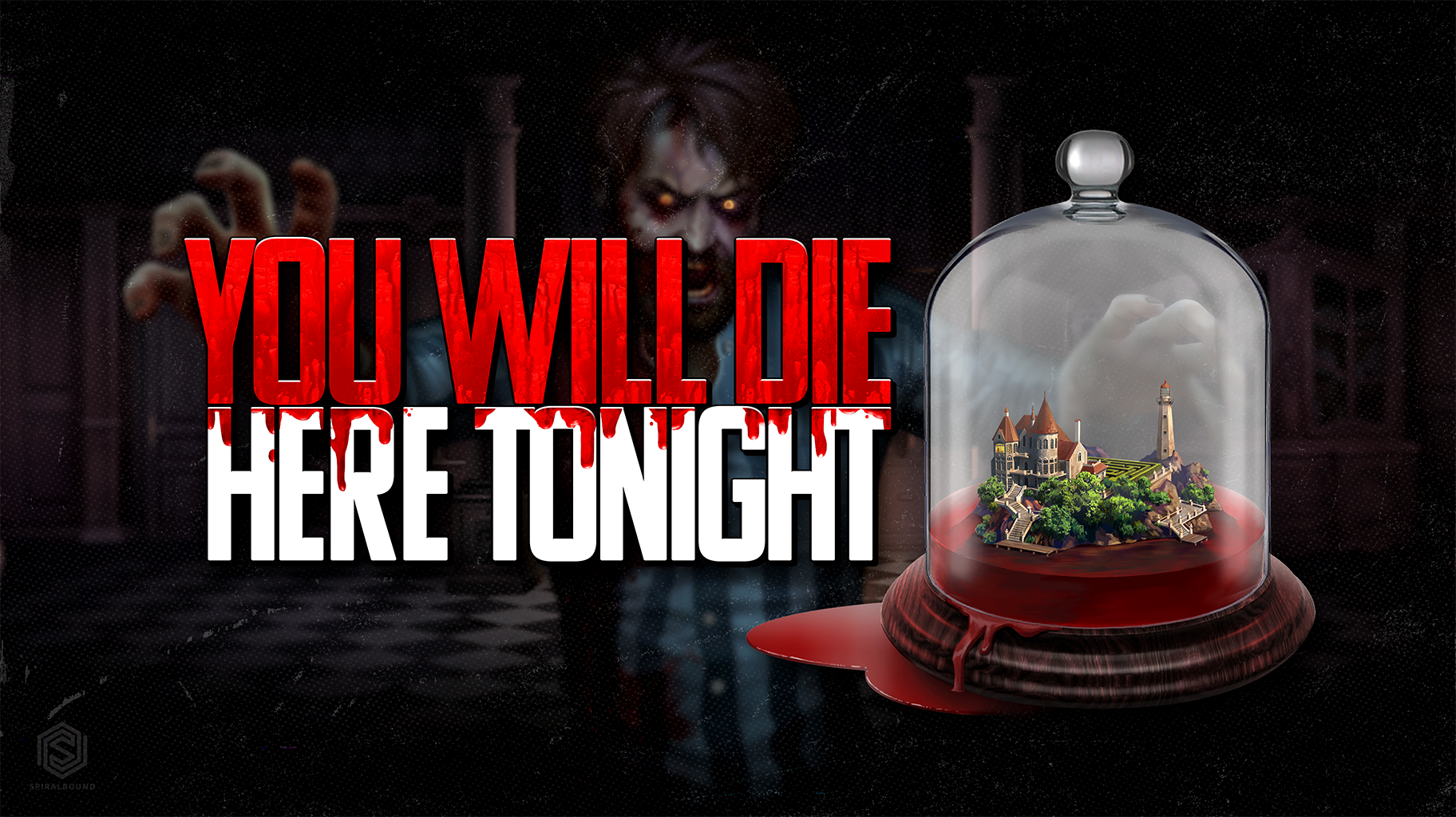

The Last Stand: Creator Chris Condon Talks About Killing Zombies in Flash for Over a Decade

Anyone who grew up playing Flash games in the early Noughties will probably have heard of The Last Stand. One of the best series to come out of the age of browser-based gaming, The Last Stand and its sequels revolved around survivors fending off the undead in a post-apocalyptic America. Starting off as a 2D tower defense-like game, the series later evolved into a side-scrolling RPG, then an isometric MMO, and now a crowdfunded 3D roguelite releasing later this year. We mentioned the games a little while ago in another article and decided that a deep dive was warranted. Speaking to series creator Chris ‘Con’ Condon, he talks about how the series has evolved from a passion project to an IP with a dedicated and passionate following.

Dread XP: How did you first get involved in game development?

Chris Condon: I started fairly young, I’d say 10 years old, by messing around with board games. I was making my own games, but mostly adjusting the rules to already existing ones. That eventually grew into getting into the mod scene around video games like DOOM and Duke Nukem 3D, making maps and replacing sprites, sounds, etc. This is where I learned the most about making games.

I kept up with working on mods and eventually while working in the Unreal Engine making maps, I fronted up to Cliff Bleszinski in an IRC chat room and showed him my work. He offered me a job pretty much straight away, so I became a “community contributor” for Epic Games for the Unreal Tournament modification I was working on called Infiltration. This was in the late 90’s so it was pretty unheard of; I was working for a company on the other side of the world to make 3D worlds, while at university in Australia.

I convinced my parents to let me leave university and work for Epic. After that contract ended, I eventually started working for a friend who had just formed a digital ad agency. I did a bunch of advertising work there, which mostly revolved around making games for the Australian Defence Force. During that time I learned Flash and found that it was possible that I could make games on my own.

DXP: Where did the idea of The Last Stand first come from?

Condon: I’ve always been a huge horror fan; I discovered the George Romero films fairly early on in life and really fell in love with the zombie genre. There’s so much crap out there in the genre and George wasn’t making any more movies, so when 28 Days Later came along, it was amazing; such a fresh take on everything about zombie films.

I’m not sure if it was during my first watch or one of the many after, but the scene where the protagonist and the army are defending the farm house, which they’ve set up defenses on – that was it, I wanted to recreate that moment. That feeling of having these things coming out of the dark toward you and holding them off. I think it’s only a few minutes in the film, if that.

DXP: How did you go about making the first game?

Condon: I started it as an attempt to get better at programming. Up until that point, I’d only done some small amounts at university and never really had a grip on it. So I just started doing it by following tutorials and borrowing bits of code from people who’d asked about the same type of thing I was running into. I had a good idea of what it takes to make all the parts work and that definitely helped.

But after 6 months or so of sacrificing weekends and nights after work – I had a game that was functional.

I initially had no intention of releasing the game to the public, so I’d just share it with my co-workers, until one of them pointed out that there were Flash portals that would pay for them. So after digging around, I found that Armor Games had a competition running with a $16k USD prize attached to it (in 2007 money this was incredible) and I entered. The game went right to the top of the voting list and I ended up winning the competition. That was the push for me to leave my job and start Con Artist Games.

DXP: The second game expanded on the first’s ‘tower defence’ formula – can you talk a bit about its development?

Condon: The Last Stand 2 was the only direct sequel that I’ve made in the series so far. It was actually a really quick turnaround, only taking an additional five months of work to make. A lot of that time was spent on the extra art and the additional travel system, which expanded on the time-based system from the first game. I wanted the game to better replicate the scavenging experience the characters would be going through, laying out a town map and deciding where their best chances of finding something were. The travelling was designed to give a bit of replayability, as you could skip over locations and weapons in each run through. I think that helped, as it gave people more choices.

DXP: The third game in the series – The Last Stand: Union City – was an RPG; can you talk a bit about what it was like trying to develop a game in a new genre?

Condon: Union City was born entirely out of my playing too much Fallout 3. I’d been into Fallout in the past, playing both of the originals and Fallout: Tactics, but man did Fallout 3 consume me. So when it came time to make another Last Stand game (I’d made a few other games in between) I knew I wanted to capture that same feeling. The loop was really simple; it was all about the looting for me. Opening every container, scanning the item names for useful stuff and then moving on would keep me entertained for hours.

Initially, I wanted to make the game isometric, but I lacked the technical knowledge of how to do something like that in Flash. So it was back to side scrolling.

In terms of tech, the game obviously needed a lot more systems, including quests, travel, and save games. This was a huge learning experience for me, but I did it the way I always had and investigated how other popular games worked. I’d say that about two and a half years of the three-year development cycle was spent on the engine, then a furious six months of photoshop and quest building.

DXP: The fourth game moved from the traditional 2D perspective to 3D – can you talk a bit about how you navigated the leap?

Condon: This was all due to the success of the previous games and some help from Armor Games to get us off the ground – I was able to grab three really talented people that I’d worked with at the digital advertising agency and convince them to come and build The Last Stand: Dead Zone with me.

The only way this level of quality 3D in Flash was possible at the time was thanks to a group of developers based in Russia called Alternativa. They had a 3D engine for Flash which they made freely available. They did amazing work to get their engine looking as good as it did.

Moving from 2D to 3D is a huge multiplier in terms of the amount of work that needs to be done. Thankfully we were still building for a web browser, so we could get away with a lot of lower fidelity assets. On the art side, for me it was like being 15 again; I was back to working with texture sizes I’d used in DOOM and Duke Nukem. Lots of tiny pixel painting.

The level design side of things was very different and much more painful. We had to build our own tools and it was all XML based. Lots of painful incorrect prop placements and mistakes. It was just a very time-consuming job.

We still managed to get a working product out in around eight months. The game then ran for nine years before it was shut down.

DXP: The Last Stand: Aftermath was successfully Kickstarted in October of last year – you can currently play a demo for it on Steam. Can you talk a bit about how you went about organizing a Kickstarter campaign?

Condon: The Kickstarter was a decision we came to when we felt that we definitely needed more development time on the game. In addition, we wanted to ensure we had great music and polish on it. It didn’t make sense for us to rush into Early Access and then have to develop the game “live” effectively.

For us, we were lucky; we’ve had friends at Kickstarter for a long time so we were able to talk to them about best practices, but most of the work for the campaign was handled by Armor Games Studios.

The campaign went well and we raised just over $60k USD. It’s been amazing; it’s made the rest of development a lot easier, not having to worry about funding as much.

Putting the Kickstarter itself together was relatively simple; it’s all about having good art and a trailer that gets across what you’re trying to do. Then it’s just about hustling in the lead up to launch and every day of the campaign to get eyes on it. That’s the hardest part. We have a considerable fan base; literally hundreds of millions of people have played a Last Stand game at some point, and it’s really hard to get your campaign in front of those people.

DXP: What’s the state of Aftermath at the moment?

Condon: The game is in great shape; we’ve spent the last few months doing a ton of Quality Assurance testing across all the platforms to get it ready for release later in Q4. It’s hands down the biggest game we’ve built and it’s only the two of us on the Con Artist side this time, but thankfully we’ve got an awesome supporting team in our publishers that’re making it possible.

DXP: What was the most challenging aspect of developing the series?

Condon: The one thing I wasn’t prepared for was community management with Dead Zone. Being an online game, we had built in chat and trade systems, PVP raids and all kinds of other mechanics that just opened up the gates of hell. The amount of problems caused by allowing players to interact with each other in the way we did was a nightmare. It was constantly a problem and ate up a lot of development time, moderation time and resources. Then we had people who were selling cheats on top of all that, so we were fighting them off as best we could as well. It was a lot. It played a large part in why we decided to make Aftermath a singleplayer Last Stand game.

I’ve personally learned a huge amount through making the series. It’s been almost 14 years since I started making the first game and it truly has changed my life. It’s a fun series to go back to because we’ve been able to flex it around and make games that jump genres, and there’s always more learning to do whenever that happens.

DXP: Are there any particular moments that stand out for you from your time on The Last Stand?

Condon: The best thing honestly has been meeting fans in person at conventions and such. Because the games have been around so long now, the series spans 14 years – I’ve had countless people come up and say “your games were my childhood” or “I used to play your games in computer class”. These are people in their 20’s and 30’s now. It’s extremely cool that I get to bring some amount of enjoyment to people’s lives and that they remember it for years after.