Painful Topics and How Video Games Handle War and Tragedy

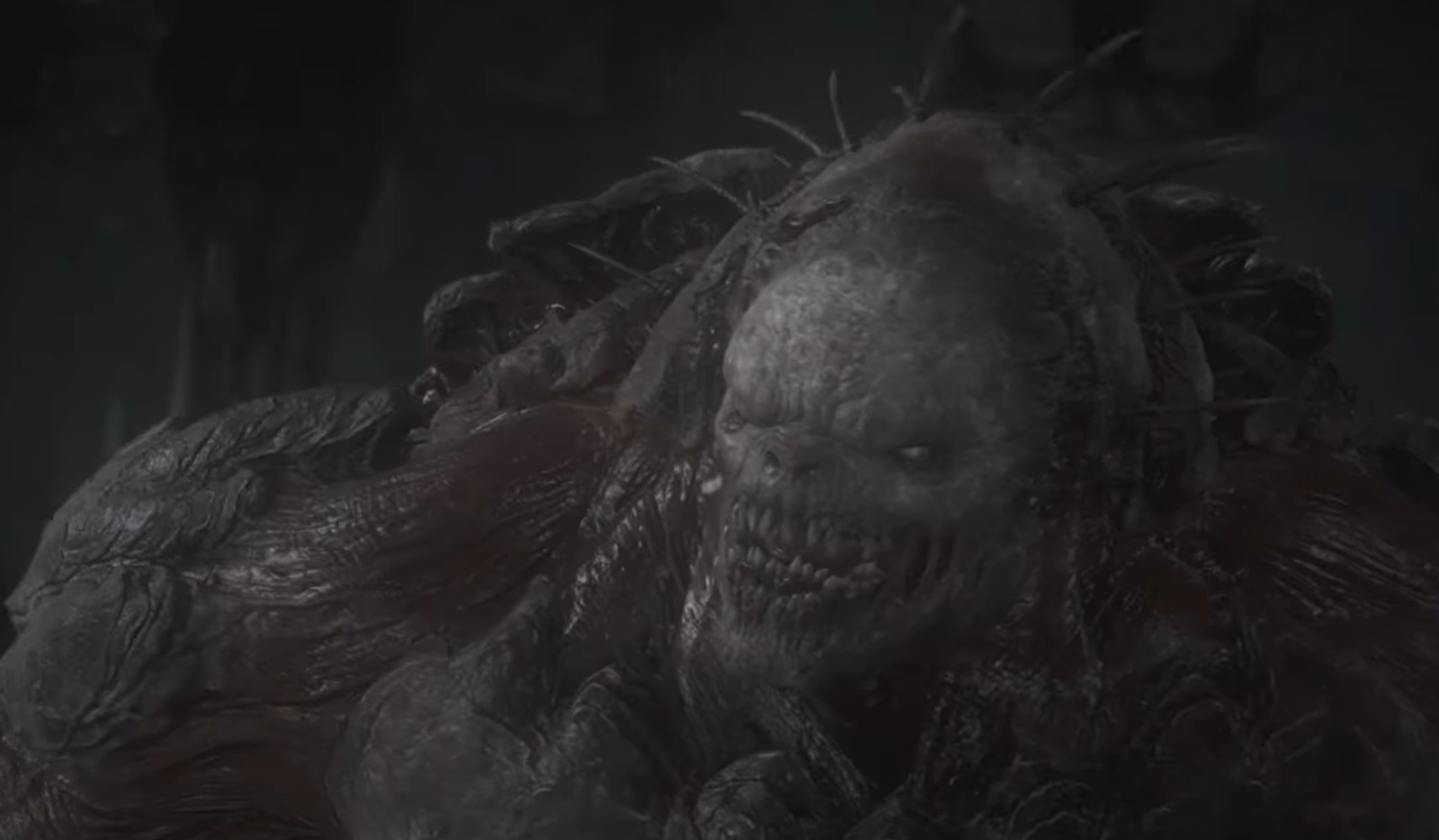

Tragedy and grief use art as a means of closure through expression, grieving, and realization. However when people think of games, even as an extension of art is less considered a vehicle for processing pain. Titles that approach themes of pain, trauma, and suffering find part of their market success in how uncommon these topics appear in games. Silent Hill stands out as a Franchise that made its mark and hit a mass following with Silent Hill 2 and Silent Hill 3 tackling deaths of loved ones, traumatic life experiences, and the fragility of the human body. It’s not all success though as other titles featuring similar themes were massive market failures like Rule of Rose due to market and authority discomfort with the content. Instead, the market is largely dominated by action games including shooter games in which war is commonly featured. It’s hard to find a game where a bad guy standing in the player’s way is removed with some tool of lethal effect.

Video games have a tenuous relationship with realism. One of the most popular franchises to lead the market Call of Duty arguably hit its apex during the Iraq war with the release of Modern Warfare 1 and 2 with the sand-swept heroes of the American Military executing middle east warlords and clandestine Russian plots. But it wasn’t just the surrounding context of 911 and America’s military campaign in Iraq that had people arguing ethics, it was the process of interpreting the violence of war as a game. Reactionary media does what it knows best and uses new media as this month’s scapegoat for domestic violence. Academically there were concerns with the game serving as a marketing tool for military recruiters and for stereotyping enemies of war with America shown as honorable and justifiable even when disregarding international law. The remake of Call of Duty: Modern Warfare was released in 2019 but has improved nothing with white phosphorous killstreaks and a fictionalized Russian war crime with the same name as one America was suspected of in real life.

Then comes along Spec Ops: The Line a title likely famous enough that readers may already know where I’m going but I’ll summarize just in case. Spec Ops: The Line begins as a typical military shooter with 3rd-person cover-based combat with levels featuring environmental traps as mountains of sand consume an apocalyptic Dubai. It’s later revealed that the story is heavily based on Joseph Conrad’s book Heart of Darkness with our jingoistic protagonist mistakenly killing a refugee camp with white phosphorous and dooming the surviving population to die from dehydration and disarray. All the while he keeps up the delusion of heroism until the very end where the big bad is revealed to be deceased making all of the ethical compromises meaningless. Despite this Spec Ops: The Line was a commercial failure, ending the franchise there even with awards for its stories and cult following for how it challenges the gun-ho attitude of modern military shooters of the early 2000s.

In 2014 a game by a Polish studio, 11 Bit Studios released. This War of Mine. A game inspired by the real-life Siege of Sarajevo in 1992. When it comes to Action games they are all about a character facing challenges and emerging stronger through found inner strength and emotional resolution, one person to change the world. This is not an action game. This War of Mine is a game about a small group of 1-4 characters from different backgrounds brought together through trivial circumstances created by the war. Where Call of Duty: Modern Warfare and Spec Ops: The Line have opposing messages they both star a Soldier and his gun sweeping away combatants. This game stars the civilians caught in the conflict, the ones who have to survive the collapse of civilizational not knowing if it when or if it will ever be pulled back together.

The character journeys in This War of Mine are similar to Spec Ops: The Line, the longer the conflict drags on the more the stress of mortal danger wears and scars their body and mind. The game becomes filled with a sense of depression, decisions revolve around what people need immediately for their physical sanctity be that the group players look after or the other survivors in the city. The mental health of the group becomes a secondary objective, as the player, it’s hard to take their troubling thoughts with much significance when starvation or illness is a day away from becoming a reality. Even once the conflict is resolved there is still weeks of silence before relief forces and infrastructure begin to recover and during that time days and night are unsettlingly mundane. In this time of relative calm, the choices and ethical compromises I made as the player began to set in.

When violence happens there’s a limit to how people are able to respond. Much of tragedy is something out of people’s control. When it comes to Post Traumatic Stress Disorder there is an emphasis on Post. It’s the memory of the trauma that relapses and pains victims. Trauma itself is different than pain. Most people understand that mishandling a kitchen knife or catching fingers in a doorway cause pain so we change our habits appropriately. But there’s no individual action that can stop a war or a random act of violence, the irrationality of pain and the lack of closure is when the pain becomes trauma and that is part of the message This War of Mine tells about war. The game becomes a space to evoke these emotions and have a space to divulge them without danger. In no way is this equivalent to professional therapy but it does help motivate a perception of trauma as a tangible part of life that does, unfortunately, occur at some point in people’s lives and they too struggle with it all the same.

For more reading, you can find other editorials and reviews here at Dread XP