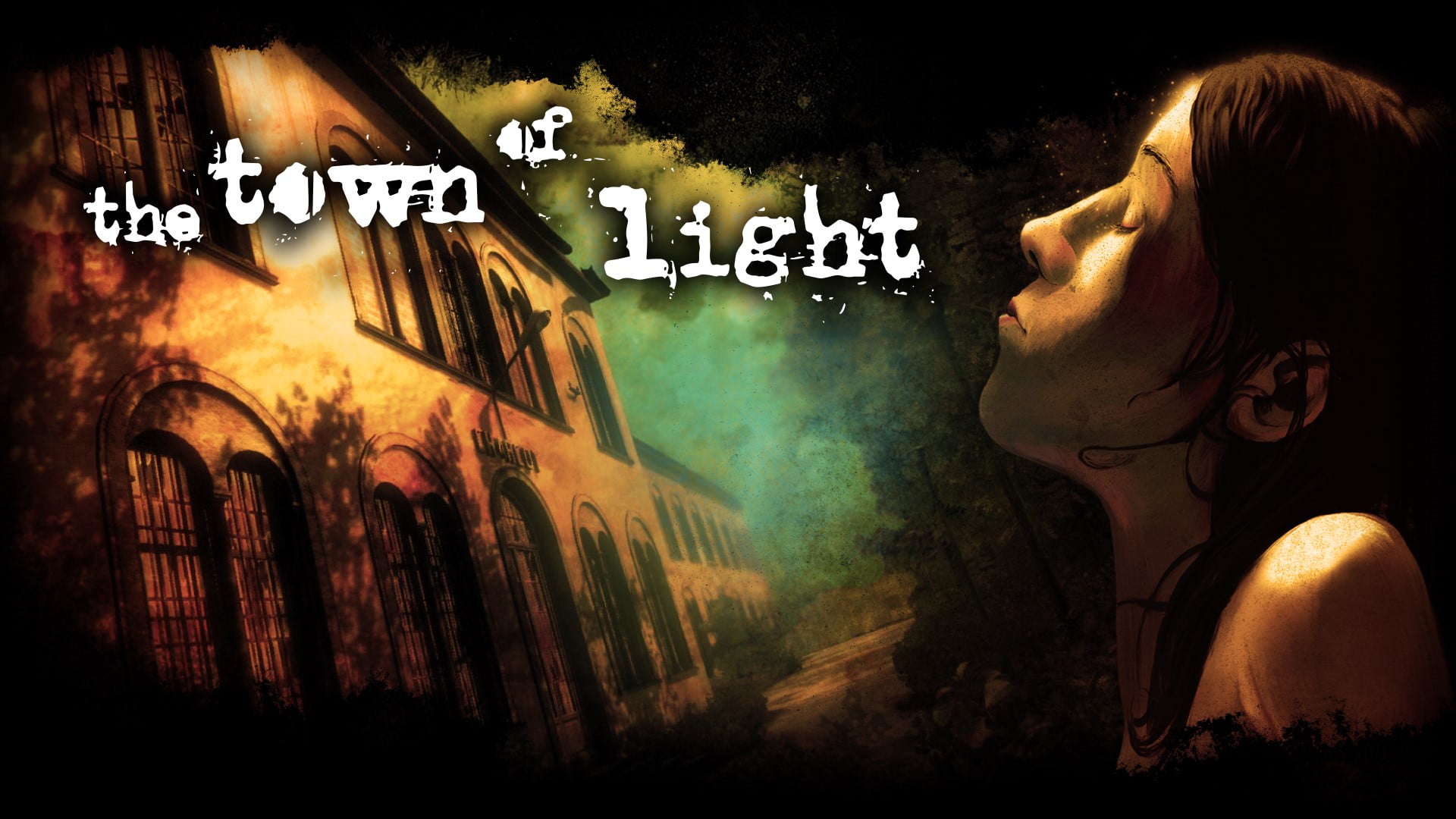

A Walk Through The Town of Light: Psychological Horror and Exploring Trauma in Game Form

I have never had a game I bought on a whim live rent-free in my brain quite like The Town of Light. Though usually priced at around $19, I paid only a couple of bucks when I bought it on sale from the Nintendo Switch eShop last year.

It was almost Halloween of 2020 and I was seeking something to scare me. At least to startle me. I wanted to get into the mood for my favorite holiday.

And sure, The Town of Light did frighten me. There are several scenes that I find myself thinking about at random from time to time. And, if all you give this title is a quick glance, this may seem an odd comment. After all, the game itself has graphics straight from the PlayStation 2 era.

This is not a review of The Town of Light. Rather, it is an exploration of the central ideas that help define this title.

Going forward, there will be spoilers. And if that frightens you, perhaps step back and try this game out for yourself. It’s been sold for as low as $2.84 on Steam, thanks to sales.

Many critics were mixed on it, but I would call it an absolutely heinously gripping game. In short, I loved it. So, if you are still with us, dim the lights, grab a blanket and a snack, and perhaps even a bucket to hurl into because this is going to be a bit of a ride.

For a brief synopsis, The Town of Light is a game by small Italian developer LKA and takes place in the ruins of the Volterra Psychiatric Hospital in Tuscany, Italy. The story follows Renée, a young girl who was involuntarily committed at the hospital and stayed there during the 1940s.

Set in the year 2016, this psychological horror adventure follows her as she walks around the dilapidated asylum, finding letters that reveal details about herself and other patients, and remembering events including lesbian romance, rape by orderlies, and – in the final moments of the game – a lobotomy.

What makes things particularly interesting is that you never interact with another human being outside of memories until the final moments of the game. While the game contains multiple pathways through it, the ending remains the same: The view shifts from a first-person POV to that of a surgeon looking down at Renée’s face as he performs a very gruesome frontal lobotomy on her.

What builds the eerie feel of this game is that we do not know if Renée is even alive or not throughout. She was committed at 16 and lobotomized at 23 – the latter for sure occurring right before the end of World War II. Though you move at a very slow pace during your playthrough, Renée’s narratorial voice is very young-sounding and almost childlike. She certainly does not seem near zombie-like, as she is described as being post-lobotomy.

I would argue, then, that you are not playing as a 95-year-old woman reliving the past – as I have seen some suggest – but rather as a spirit, lost and trying to find what happened to herself in life. This seems to line up with how the game presents her as well.

Though she is still technically alive after her procedure, in the final cutscene, it seems as if the light has faded from her eyes. This can be interpreted as, though still shambling through life, her soul had died in the operating room at 23.

This also lines up with the beautiful panorama that is displayed during the ending credits. Renée fades away and we see not only a spectre of herself, but a pan through the entire grounds of the mental hospital with all of the patients and orderlies represented as ghosts – lost and wandering aimlessly. This is all presented in a gorgeous shade of muted tones.

Speaking of aesthetics, though the main game has some very basic, perhaps PS2-esque 3D graphics, the memory cutscenes, and the ending scene are beautifully illustrated. It is as if the overworld is merely a means of interacting with the story, while the cutscenes, in their detailed beauty, bring the story to life.

What is a fact of this story is Renée is an unreliable narrator. Sure, there are some facts that are potentially known for certain by the end of the game. Her age. The fact her mother died. The fact there was a fellow patient named Amara with whom she was close. And disturbingly, the fact she was often the victim of physical abuse, including being tied to her bed for days at a time and being subjected to electroshock therapy.

But, you could also argue that several other facts are the processing of a confused spirit who is trying to remember what happened to herself. After all, much of what was just listed is not said by Renée herself but is revealed to the player through letters and medical documents found throughout the game.

For example, it is shown that Renée and Amara have a sexual relationship in Renée’s memories, though it is both shown and implied that Renée often spent her time alone talking about or to Amara, even when she was not there. Though it is confirmed they were close in life, the sex can not be fully proven or disproven.

In addition, Renée is shown to be incredibly close to her doll, Charlotte. An early section of the game even involves wheeling the worn doll around the remains of the hospital in a wheelchair, and even restoring power to the building just so that the doll can sit under some warm lights. Renée does not see Charlotte as a toy. Instead, she sees her both as a tangible connection to the outside world, and even as an extension of herself.

Before we continue on, I should note that is merely an examination of Renée’s depiction as a character and as an effective vehicle for showcasing horrific circumstances (such as graphic lobotomies and torture) to the player. This does not, however, discount the horror of what was actually experienced by people like her.

The Volterra Psychiatric Hospital was – and currently is – an actual hospital in Italy. It was originally closed in 1978 as part of a mental health reform initiative in Italy but was reopened in 2018. Fittingly, it early on gained a reputation for the horrific treatment of patients there.

In The Town of Light, Renée at one point described being tied to her bed in a room of other patients, their screams constantly filling the air. Mostly, this is due to them being roughly handled and even choked by hospital staff.

At one point a woman nearby throws up, chokes on her own vomit, and dies. And the corpse of the dead woman is just left there for a bit. The staff is in no rush to check on her. The whole room erupts into screams.

The knowledge that this is based on reality is maybe the most terrifying part of The Town of Light. As a player, you see this young woman be committed after being molested. You see her be abused by doctors and other patients, have her communication with her family limited without her consent, and even witness her go through a forced abortion.

As terrible as it is, and as graphic as it is – especially after you see the terror in her eyes as a pick is shoved into her brain by a doctor and tweaked around so that she becomes a disoriented, shambling shell of a young girl who is described as seeming dead inside – this is all a representation of things that actually happened in mental hospitals in Italy during that time. Actual people experienced all of this.

A full medical description of how a lobotomy is performed is read in the final scenes, along with the history of the procedure’s use in Italy. Renée is representative of an unknown number of people who went through similar things.

This is what truly makes The Town of Light a masterclass in psychological horror. It’s graphic but never bloody. It is shocking but lacks a single jumpscare. It has depictions of acts of monstrous proportions, but Renée, outside of her memories, never interacts with another living thing. It looks like a title from several console generations back, yet presents an experience that is oddly visceral.

Yet somehow, it finds a basis in reality. A root in history. A home in the minds of those who play it. And this Halloween, this is one I look forward to playing through again.