Link to the Past Uses Horror to Make its Adventure Truly Memorable

The Legend of Zelda: A Link to the Past was my first taste of adventure in a wide-open world. Doing heroic deeds in Hyrule was exhilarating in ways few other games could capture at the time. This game was also one of my first experiences with fear and horror as well, though. While action, puzzles, and exploration were a big part of the mood of the game, with the transition into the Dark World, the game took an unsettling turn. One that made for one of the most memorable, resonant adventures in the series.

During the first part of the game in the Light World, you’re chasing down magic pendants to get access to the Master Sword. Gotta thwart evil with a magic blade, right? Everything is bright and colorful, and the stirring music carries you through thrilling action against your various foes. It’s all very upbeat as you draw the Master Sword and proceed to defeat the evil wizard at the top of Hyrule Castle. However, you soon find yourself in a land far bleaker than anything I expected.

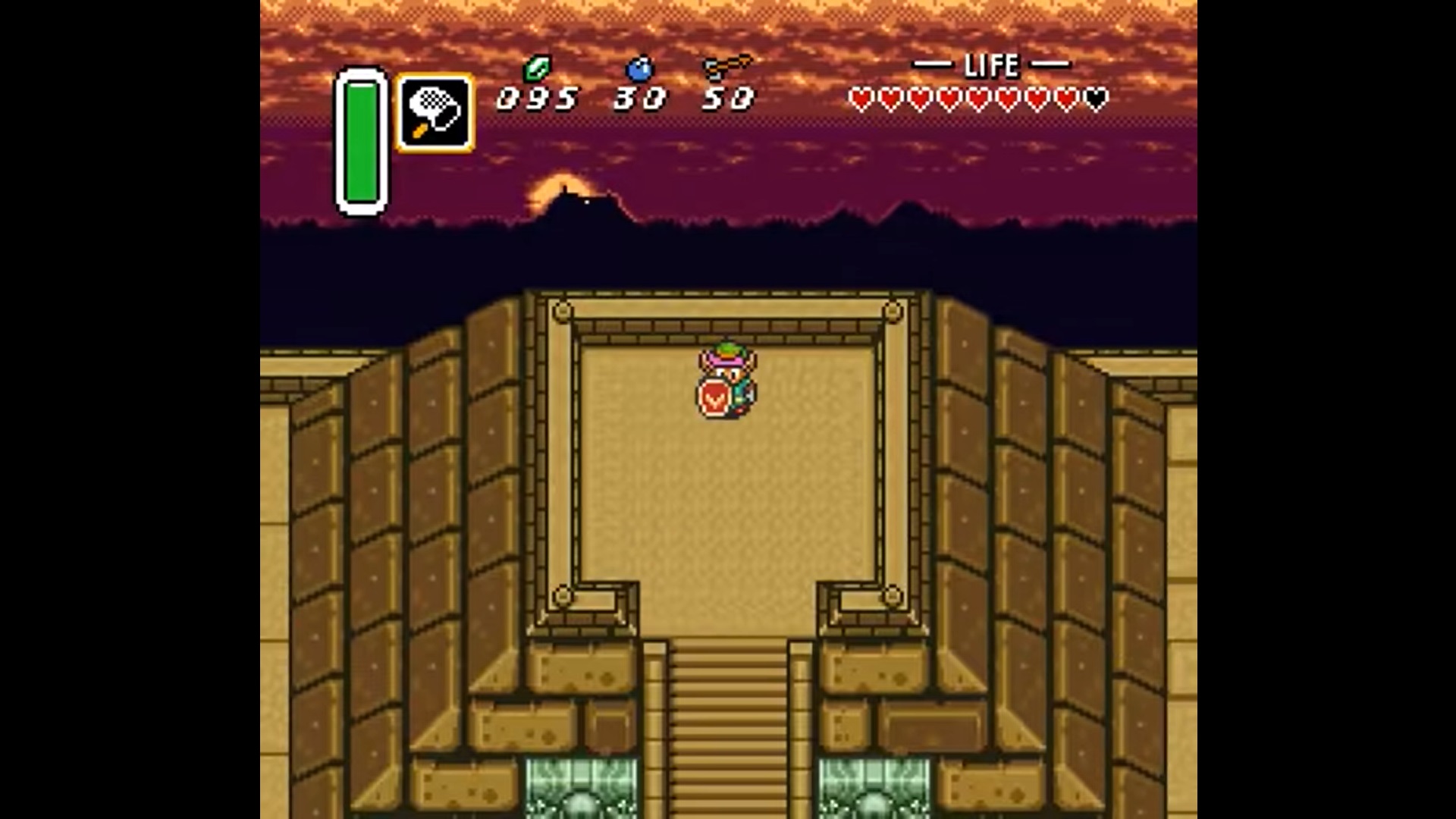

The Dark World is a ruined realm within Link to the Past. When you first land here, you can sense the poison within the land immediately. The shimmering and brilliant shades of Hyrule has been replaced with a blood-red sky and noxious orange clouds. As you step further into the world, you can see more evidence of the monstrous powers at work. Everything within it is decaying, mis-colored, or mishappen. The tree have strange faces that spit bombs at you. Wild skeletal animals wander between broken homes. Thieves dog your path. The world itself feels infected. Malicious.

With your entry to the Dark World, it feels less like you’re on a thrilling journey and more that you’re trying to survive a hostile land. Stone skeletons, twisted statues, and other macabre art pieces line your path as you walk. As I said, even the trees spit bombs at you. It’s all made to look and feel like everything in this world is dying or monstrous. It creates an unease that feels wholly new, and it makes you feel more uncertain in your ability to win. Back when everything was upbeat and bright, your victory felt assured even in hard times. Here, you can’t help but feel that you’ve already lost and just need to own up to it.

The monsters and bosses will drive that feeling home if the look of the land doesn’t. The first time you land in the Dark World in Link to the Past, you probably won’t live long. Even the most basic of foes will chew through your health in a few hits, resulting in many quick deaths over small mistakes. In the Light World, you can take a few bumps and still be all right. Here, the cyclops and carnivorous plants will gouge the life from you. Those quick deaths make those heroic encounters with enemies far more nerve-wracking than ever before. You hesitate when you used to bravely charge in.

The monster designs strengthen that unease. You’re not fighting knights and irate wildlife any more. Now, you’re dodging explosives while trying to hit the massive Hinoxes. Desperately running from Like-Likes so your shield doesn’t get eaten. Darting from the hand-like Wallmasters to keep from getting dragged back to the dungeon entrance. Wallmasters somehow seem even more uncomfortable to encounter now that I’ve played Elden Ring, too. And among these examples, they don’t only hurt you badly and look bizarre/unsettling, but cost you progress and valuable items. You can lose a whole lot more to these disturbing foes than just health.

Link to the Past draws up a sense of disgust with some of its bosses as well, furthering that sense of horror within the Dark World. Arrghus’ single eye glares at you from within a pile of growths you have to rip from its jellyfish-like body in order to hurt it. Mothula trickles caustic poison throughout its arena as you try to set it alight. Blind the Thief screams when exposed to sunlight, unveiling a ghost that strikes you with disembodied heads. And if you haven’t had enough of weird eye monsters, Vitreous sends detached eyes at you from a pool of goo and eyeballs. This game loves weird eye monsters.

Many of these foes are offputting or bizarre, a far cry from the statue knights and nasty wizards of the Light World. While there are some gross monsters in that world (Moldorm the massive worm is pretty icky), here, it feels like you face more sickening, unsettling creatures constantly. The kind of things that have you tearing off body parts, stabbing eyes, or dodging thrown heads. It’s far more macabre than the first half.

It’s this lean into horror that made Link to the Past so memorable, though. When that sense of adventure came easily in the Light World, I didn’t notice it, really. I was feeling the thrill of it, and being carried by it, but I never took notice of the shining world around me. Didn’t really notice that my heroic victory felt certain as powerful music carried me across the countryside. Once I was mired in the Dark World, though, I became more aware of that bright nature of the Light World. I could appreciate the cheerful people and scampering wildlife, because I had seen the grim alternative. Its contrast makes your work toward saving the world feel that much more important.

The challenge and monstrous foes also make your fight feel more exhilarating, too. Victory feels like its far harder earned. The things you face make you feel a bit more fear when you fight them. Overcoming that fear and saving the day anyway makes it feel much more fulfilling, though. You can’t help but feel your pulse pound as you skirt death as you face the enemies and bosses. And eventually, you get strong enough to win in this hellish place. You feel all the more powerful and fulfilled for it.

Link to the Past takes you to a shining realm of heroism, but it’s when it drags you into the darkness that you learn to appreciate the world you’re trying to save. It’s that tumble into terrible danger and ruin that helps forge your strength into something truly world-saving. Drawing from horror, disgust, and unease make your quest resonate far more with you than if you’d always walked in the light.