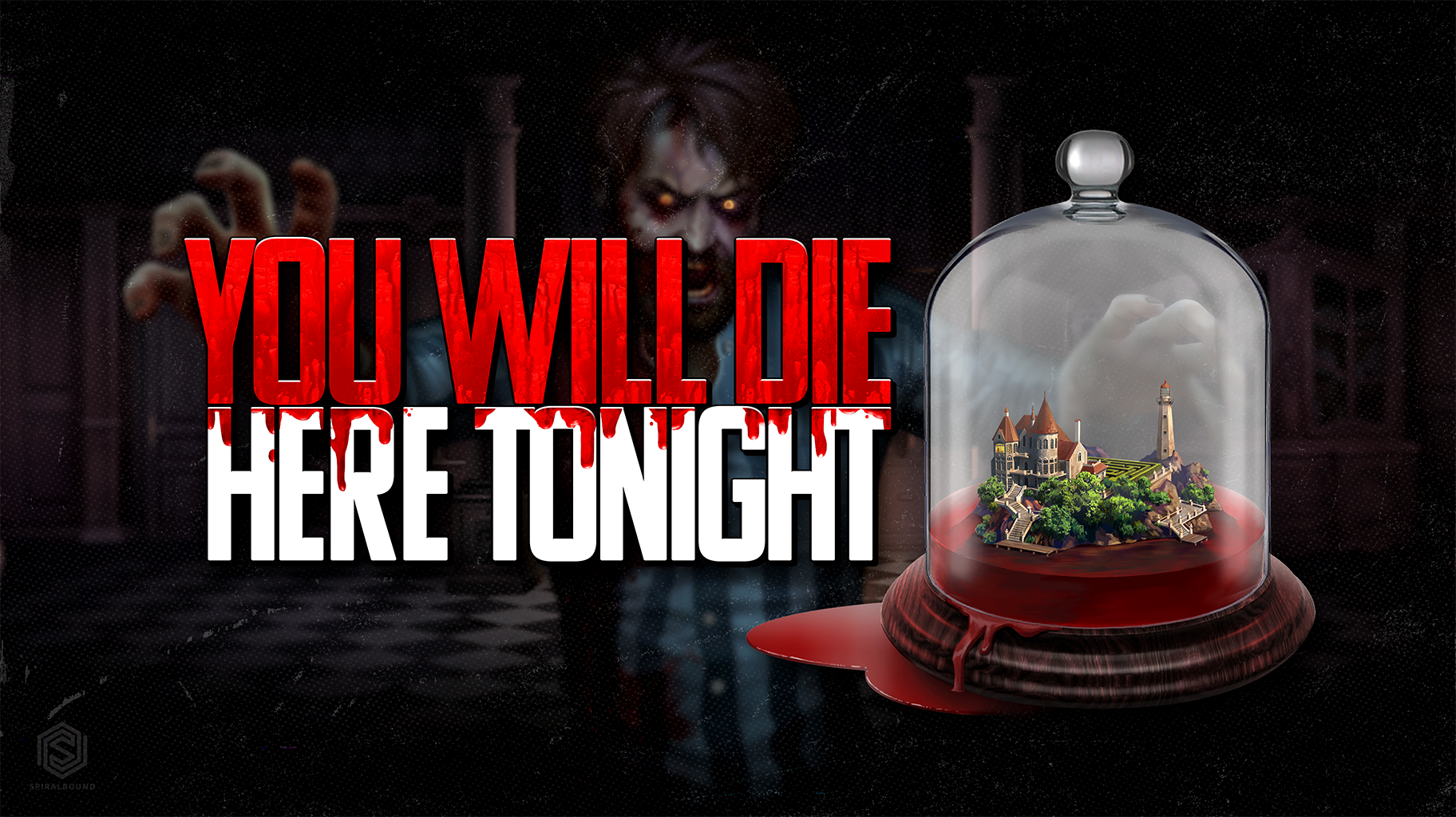

Beware the bogeyman: what makes a horror monster scary?

Most horror games are nothing without their monsters. But what makes for a compelling monster? What separates the true creatures of nightmare from the bland also-rans?

To answer this question, we’ll first need a working definition of what we mean by a monster. At its broadest, we could say that a monster in a horror setting is anything that serves as a source of fear. It can be an alien or a demon, but it can equally be a human being, a virus, an animal, or even an inanimate object. It could be a toy, or a house, or an entire location. If this is a bit too general, we might also add that it’s something with a sense of agency; something that acts to produce a particular result. While a murderous hound or a possessed town could be a monster, for example, a lifeless corpse or a creepy environment wouldn’t be.

So what makes a monster scary? Well, that depends on the type of monster. Arguably, most – if not all –monsters exist on a spectrum between two camps; the beast within, and the beast without. It’s how well a monster embodies the themes within these categories that determines whether it manages to scare or not.

The Beast Without

Let’s take the beast without first. Imagine a prehistoric tribe. They sit in a cave, huddling around a campfire for warmth. Beyond the cave, the night is cold and dark. Something howls out there, a sound that’s full of hunger and danger. That is the beast without. It is the unseen thing; something that we know is not us, but that represents a threat to us.

The majority of horror monsters tend to be of the beast without kind. Many follow this archetype in a literal sense, taking the form of creatures with the properties of natural predators. They have fangs and claws, flashing eyes, and bloodthirsty growls, and are far swifter and stronger than any normal human being. The threat they represent is direct; they seek to maim and kill. Werewolves are the obvious example, but other monsters abound, like Resident Evil’’s bioweapons or the lizards from the Dino Crisis series. Of course, human adversaries can also often be direct interpretations of the trope, especially in movies and video games. Masked maniacs or ax-wielding killers may only be mortal men and women, but when they go about their grisly task with an inhuman single-mindedness, they often appear closer to deadly machines or animals than actual people.

This straightforward approach to the beast without archetype has created some iconic creatures, from Resident Evil’’s Lickers to Jason Vorhees to H.R. Giger’s Alien. But if there’s a problem with this method (besides how ubiquitous it is), it’s that it rarely creates a horror that lingers. These monsters are the hunters; you the hunted. It’s a situation that offers very little room for psychological terror. Rather, some of the best instances of the beast without are those that have embraced one of its key components: a fear of the unknown. These are the horrors whose existence is only half-hinted at, whose threat is all the more terrible because of its obscurity.

The patron saint of this, of course, is H.P. Lovecraft. Lovecraft’s works presented entities that were truly ‘other’ in all senses of the word. It wasn’t just that they were alien; writers like H.G. Wells had already begun to explore the possibility of extraterrestrial life before him. It was that they were alien in a manner so profound as to be frighteningly incomprehensible. In Lovecraft’s stories, his protagonists are only ever given brief insights into unknown and unknowable cosmic orders of being, although even these are enough to convince them that the universe is far more nightmarish than they could have imagined. This is the power of the fear of the unknown. It – and the monsters through which it is conveyed – undermine our sense of security, by both showing us the limits of our perceptions, and then by placing the hidden danger just on the other side of them.

The Beast Within

At the other end of the spectrum is the beast within. If the beast without embodies our fear of the unknown other, then the beast within embodies the fear of our own nature. It’s the part of ourselves that we don’t want to admit exists; the dark, ugly side of humanity that we try to ignore or suppress. Sometimes, these monsters serve as a reflection of the flaws and failings of a specific individual. The titular feline in Edgar Allen Poe’s The Black Cat is a good example of this, as the formerly peaceful animal slowly comes to embody the narrator’s self-destructive alcoholism and violence. In games, Silent Hill 2’s Pyramid Head is likely the most well-known version of this archetype. Pyramid Head is a literal manifestation of James Sunderland’s repressed guilt and lust, and forms a central part of that character’s narrative arc as he confronts these feelings.

A beast within monster can also be the central protagonist. This type of monster usually occurs in games where the audience isn’t aware of a character’s true nature, or where a particularly heinous act causes the protagonist to become monstrous in the audience’s eyes. Games featuring amnesiac protagonists often create these types of monsters, as do games where the protagonist has some seemingly noble (or at least justifiable) goal, the attainment of which results in the suffering of others.

More often, however, a beast within-type monster embodies wider themes about a particular society or the human condition at large. Probably the most prominent version of this is the humble zombie. On the one hand, zombies remind us of that most universal of fears: our fear of death. Their fate is our fate; their rotting frames are woven from the same mortal tapestry as our own. They are inevitability personified, and no matter how fast you run or how sturdy your defenses are, they’ll always find you in the end. On the other hand, zombies are also often used as a vehicle of social critique. In most zombie stories, it’s the living rather than the dead that are the real monsters, as the remaining humans succumb to their baser instincts as order and stability crumble. Here, the zombie apocalypse serves as a reminder of how ephemeral our modern sensibilities are; how laws and morality get swept aside when there’s no more food and the lights go out.

The beast within monster is often tightly tied to the culture from which it arises. Monsters from the Gothic tradition, for example, usually embodied the fears and concerns of Victorian society. Bram Stoker’s Dracula drew on the prevalence of disease (particularly cholera) and the persistence of superstition in the face of scientific progress. Robert Louis Stevenson’s Mr. Hyde reflected the early advances in chemistry and the temptations of behaving in ways other than that expected of a gentleman. Both monsters transgressed the heavy taboos around sex, especially sex out of wedlock. But while these monsters remain famous, their power to frighten has greatly diminished with the end of the Victorian age. Instead, new monsters have taken their place to address modern themes. American Psycho’s Patrick Bateman, for example, stands as a critique of the amoral world of investment banking, while the amphibious creature in Bong Joon-Ho’s The Host serves as a commentary on environmental pollution.

The Beast Uncanny

Sitting somewhere in the middle of the beast without and within is a final category: the beast uncanny. The uncanny is the place where things that should be familiar to us become strange and off-putting. It’s where something has a greater or lesser resemblance to the normal and recognizable but has been skewed in such a way as to give an unshakeable aura of wrongness. Works of surrealism, particularly the films of David Lynch and Shinya Tsukamoto, are often steeped in the uncanny, creating a sense of unease and paranoia even when there’s nothing monstrous onscreen.

In the horror sphere specifically, artist Junji Ito uses the uncanny to create deeply unsettling stories and imagery in his manga stories. Rather than relying on stock horror tropes like vampires and werewolves, Ito works – in his words – by ‘taking something ordinary and looking at it backwards’. In most pieces of visual entertainment, characters are drawn to look either cool, sexy, or cute. Ito’s panels contain none of those things. Everything in them suggests a warping or distortion so that even something as mundane as a house cat can end up looking bizarre and terrifying. He is particularly adept at applying this method to the human form, creating works of body horror where the flesh itself becomes shockingly alien and repellent.

In games, probably one of the best examples of an uncanny monster is Jack Baker from Resident Evil 7. For most of the game, Jack is an unstoppable juggernaut, pursuing protagonist Ethan Winters across the Baker Estate relentlessly. But that isn’t what makes him uncanny. Other Resident Evil monsters like Nemesis and William Burkin have filled similar roles. What makes Jack disturbing is his characterization. Jack has a personality, a demented demeanor that’s equal parts sadism, good ol’ boy humor, and paranoid patriarchal protectiveness. He’s an actual person, and as such, we feel like we should be able to reason with him somehow. That we can’t – that he’s clearly operating on some insane bizarro logic inscrutable to us – is what makes him such an effective villain. In Jack, players encounter a total breakdown in communication with another (outwardly) human being, transporting them firmly into the territory of the uncanny.

The Devil You Know

Wrapping up, let’s recap the types of monsters you can see in horror. First, there are the monsters that represent straightforward physical threats to life and limb. These tap into our primal fear of physical harm, but don’t usually offer much beyond this. Next, there are monsters that play on the fear of the unknown. Although they also represent a danger, this danger is often obscure or hidden in some way, disempowering the audience by robbing them of the ability to comprehend it. Alternatively, some monsters are used to personify the very human flaws of a particular character, or can even be the central character. Still, others are used to represent a negative aspect of society or humanity but tend to be rooted to the culture from which they arise. Finally, some monsters create fear through the uncanny, by taking something that should be ordinary and distorting or corrupting it.

Horror designers looking to create effective monsters should thus try to work out what sort of fear they’re trying to evoke, whether it be a fear of the other, the uncanny, or ourselves. By drilling down and studying the best examples from each category, we can hope to see new and terrifying monsters crawling out of the darkness in the future.